A PHOTOGRAPH IS ONE POINT ON A MAP

![]() When I find myself out here in the wilderness, I take photographs to figure out where I am. I have given up on trying to take “good pictures.” I just let life show me what I need to take pictures of.

When I find myself out here in the wilderness, I take photographs to figure out where I am. I have given up on trying to take “good pictures.” I just let life show me what I need to take pictures of.

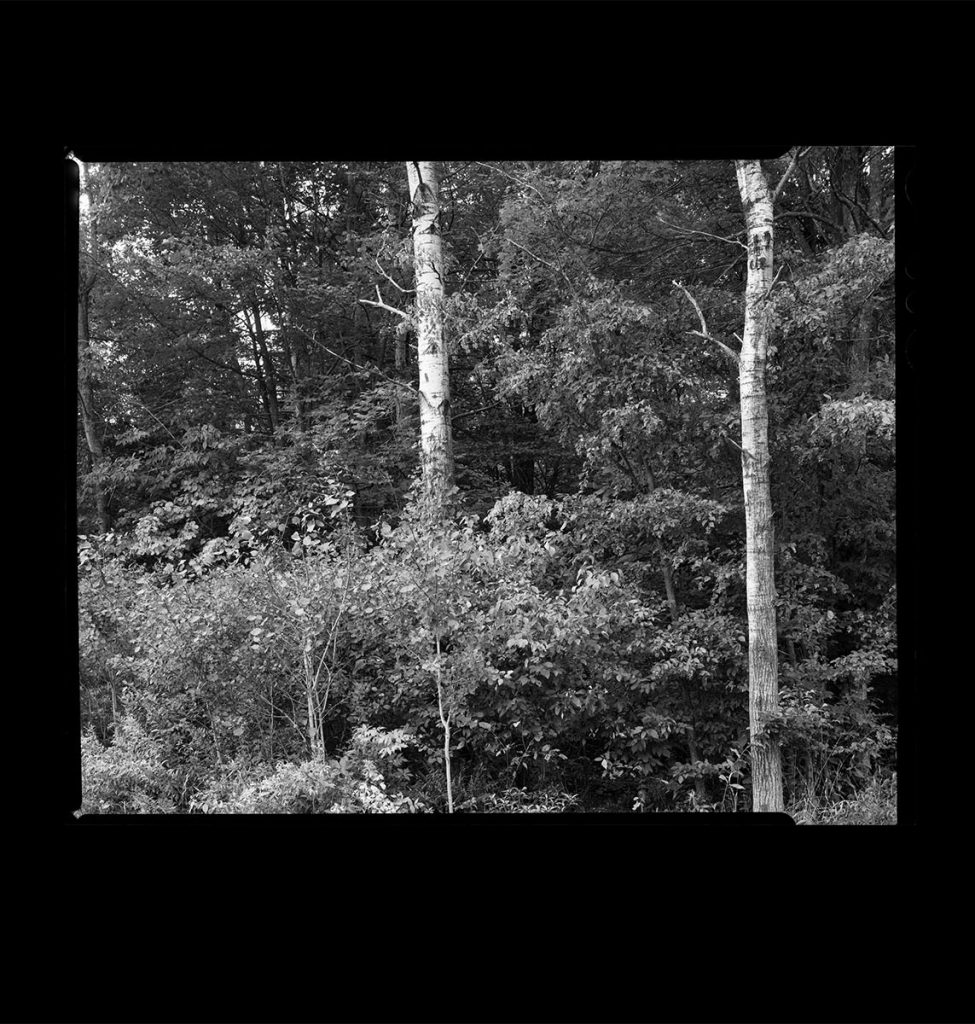

Here’s an example: my father died when I was twelve. Nearly forty years later I decided I wanted to see the ranch where he grew up—several thousand acres in Sonoma County, California. I consulted the county maps in Santa Rosa and asked the present owner if I could spend 10 days there on my own. He agreed and I took a view camera with me.

My history with a view camera was not happy. I was too familiar with Ansel Adams and Edward Weston and Minor White. This time I had the sense to leave those guys behind. What I wanted was more mundane than their version of sublime nature. All I was after was some trace of my father, some view that he had seen every day, some stretch of ground he had run over, some rock he had picked up and thrown. Now the view camera was simply a tool. It wasn’t good pictures I was after. It was location, it was evidence.

I grew up on Life magazine during the war – WWII. When my father died, mother went back to art school for a couple of summers, studied with Minor White, and subsequently made her living as a portrait and wedding photographer. She brought home Beaumont Newhall’s History of Photography and early issues of Aperture. Her descriptions of class were laced with names like Ansel and Imogen and Dory, who visited their class. They took trips to Point Lobos to see Weston. She had books of Cartier-Bresson’s photographs and Paul Strand’s and Ansel Adams’. Everyone was talking about Edward Steichen who was selecting photographs for the Family of Man at MoMA. I wanted to join that group, and for years tried to make their work mine.

In the meantime, life kept happening. I dropped out of architecture school, married at twenty, raised three kids, got a BFA in my forties, and then an MFA, left my husband and started looking for a teaching job.

Shortly after my mother died in 1978, I finally admitted that I was really much more attracted to women than to men. This was just before I entered grad school, where I was introduced to all kinds of theory, and as it happened, was surrounded by a group of very cool lesbian students.

Theory and ideas about gender, sexuality, identity and ways of seeing led me to the world of the studio. There I had complete control over what things looked like; I didn’t feel self conscious about having a camera; and I could explore my place in the world of ideas. I discovered the joys of using theory as a springboard for making work, and of making things, collecting costumes and props, and transforming myself. I worked completely alone and produced a number of bodies of work about the construction of gender, about aging and about domestic life.

One Year, 2012

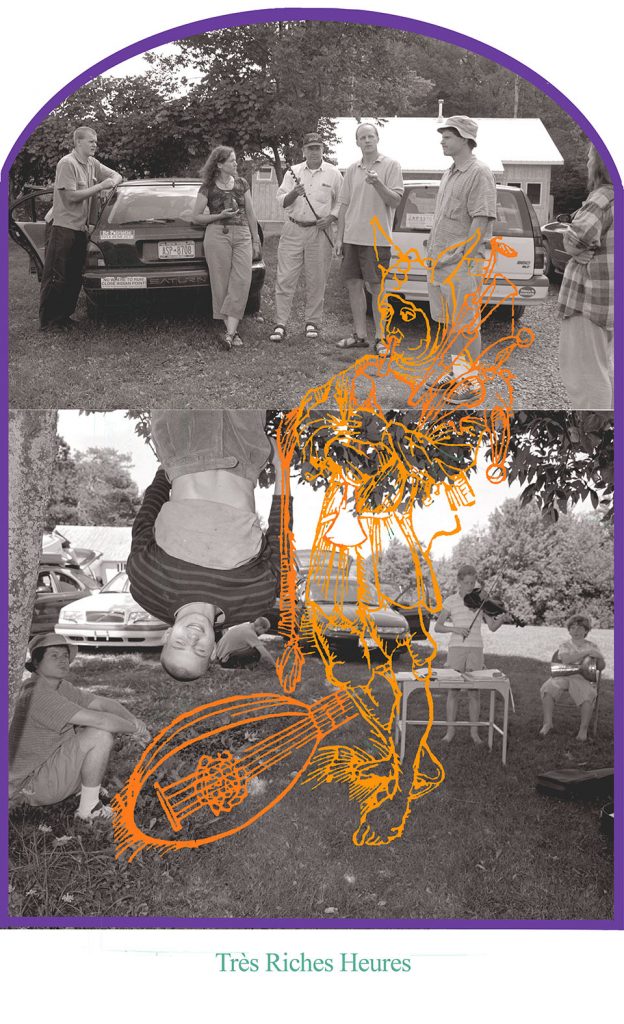

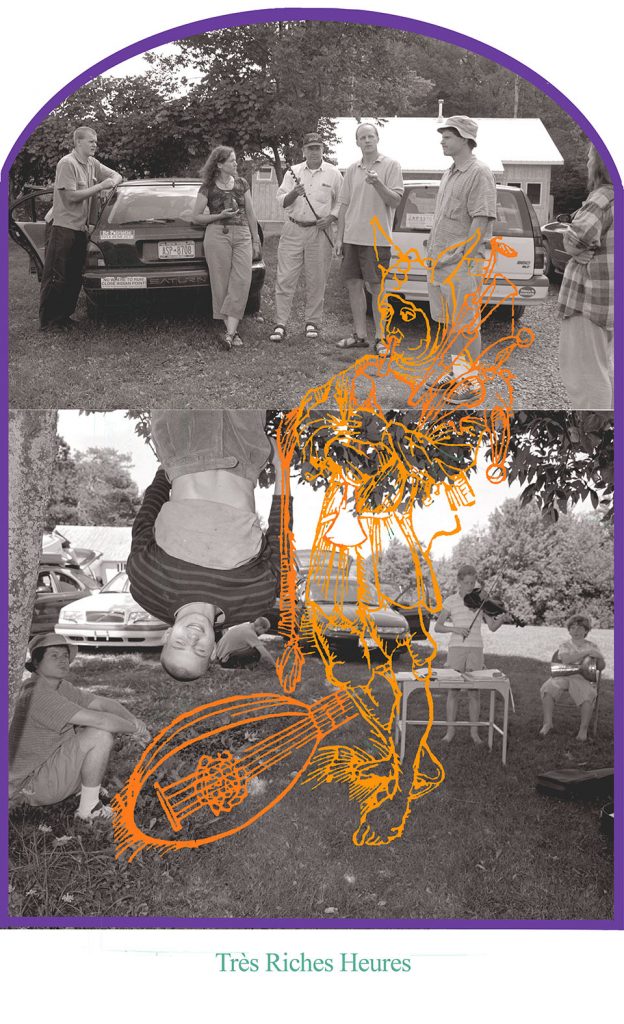

Tres Riches Heures, 2005

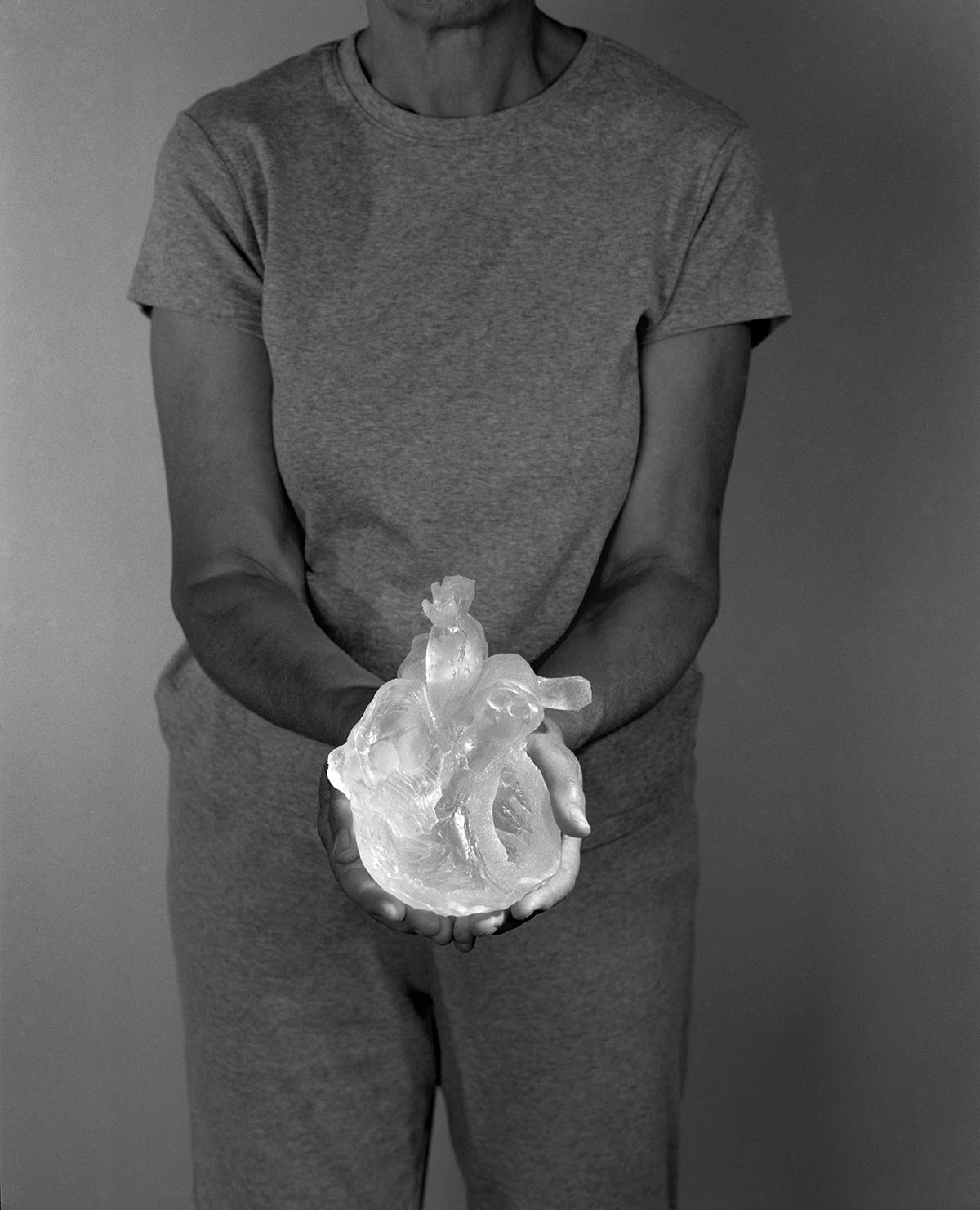

After All, 2002–2003

NoMan’s Land, 1998

Forever, 1986

Boxes, 2014

8-Acre Field, 2012

Oregon Hill, 2011

Vertical and Horizontal, 2004

The Cosmic Dominatrix, 2000–2001

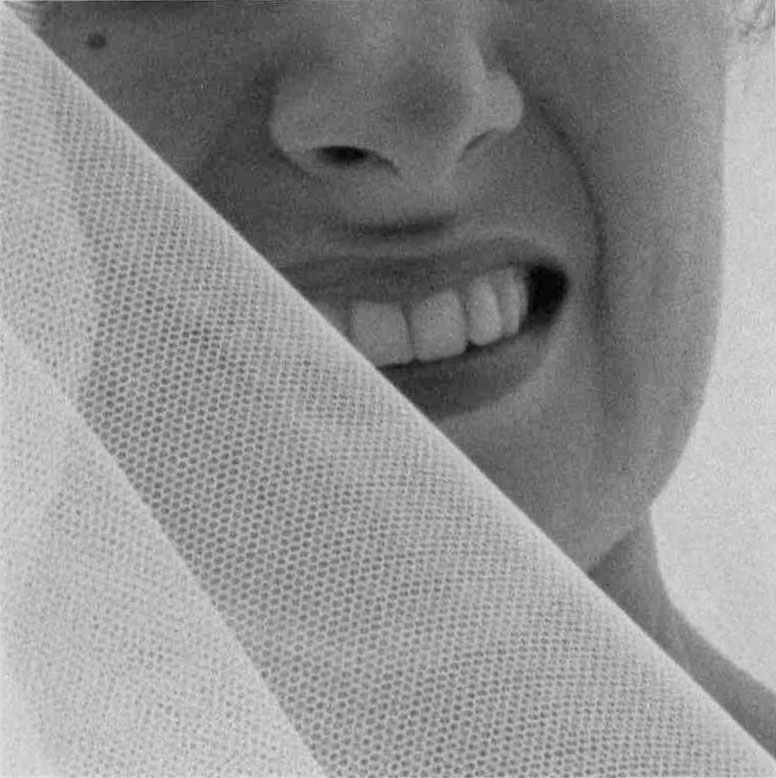

The Tomboy Suite, 1996

Claiming the Gaze, 1991–1993

Boxes, 2014

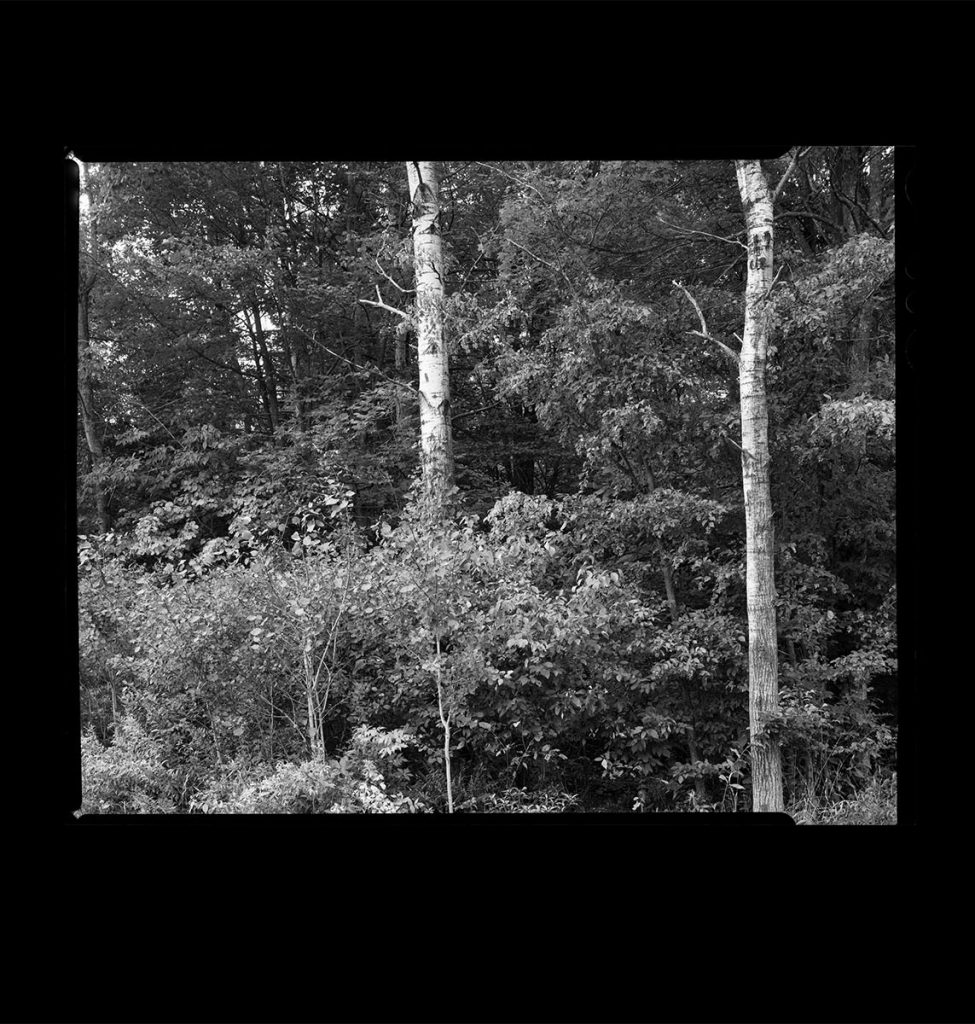

8-Acre Field, 2012

One Year, 2012

Oregon Hill, 2011

Tres Riches Heures, 2005

Vertical and Horizontal, 2004

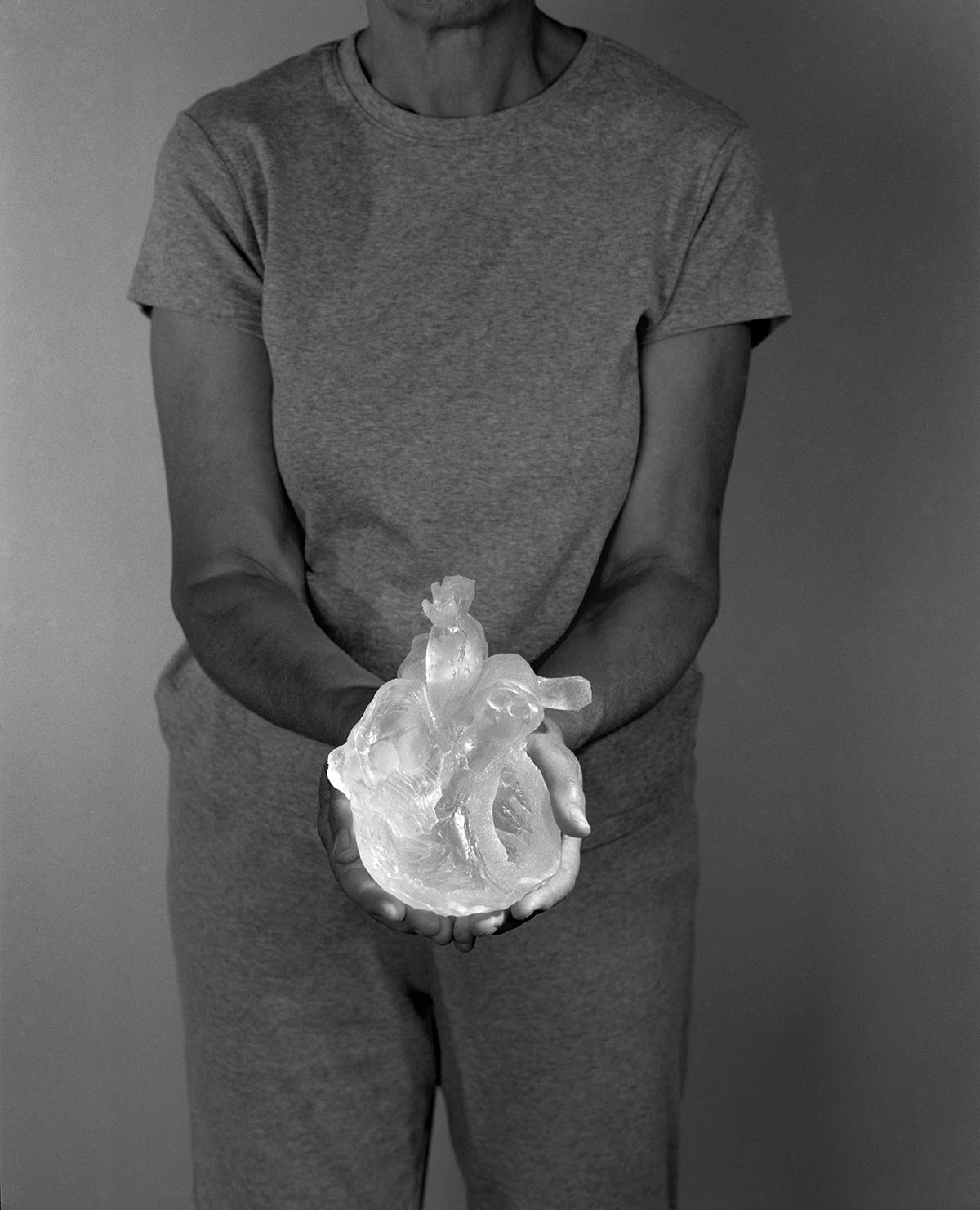

After All, 2002–2003

The Cosmic Dominatrix, 2000–2001

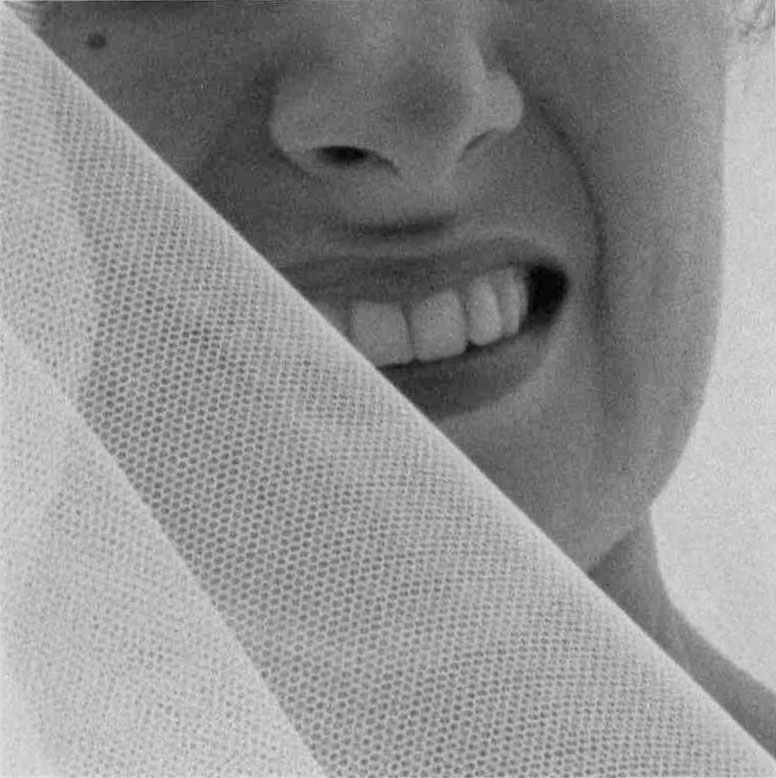

NoMan’s Land, 1998

The Tomboy Suite, 1996

Claiming the Gaze, 1991–1993

Forever, 1986