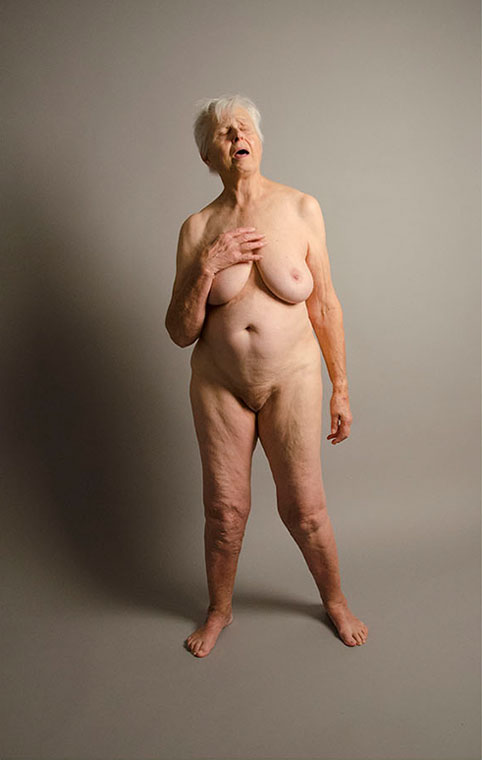

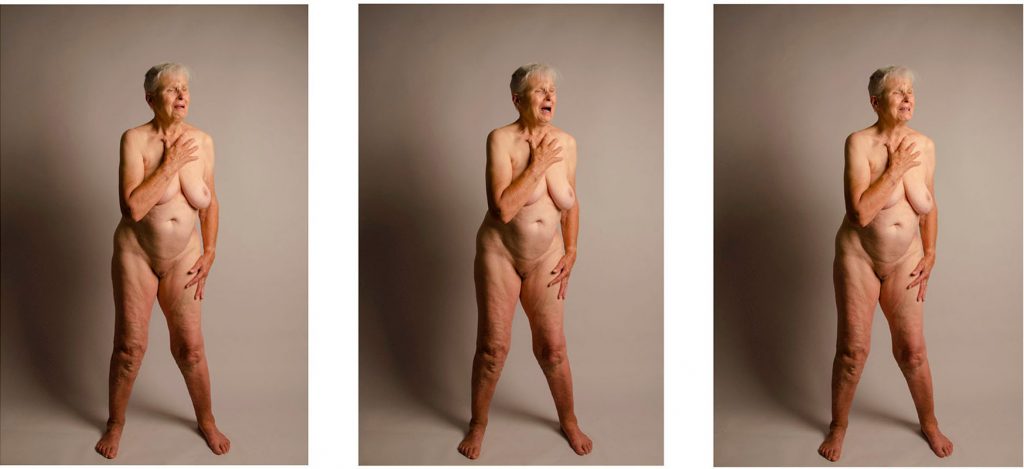

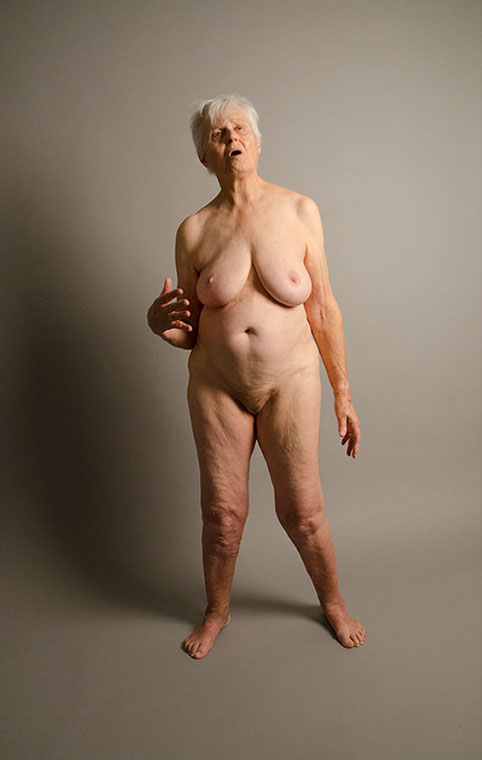

LAST STANDING, 2016

Sing (2)

Sing (2)Archival ink jet prints, dimensions below

I began making this work, Last Standing, shortly after the death of my older sister in August, 2015. That death left me the last standing of my family of origin: two parents, four daughters, all gone except me.

Cry was the first of the series, a simple statement of grief at the loss of someone dear to me who had known me from the beginning. A straight forward gesture, but also a taboo, at least in my family, where grief was a private emotion, never on display. A moment after she died I stood in her bedroom where she still lay on the bed, surrounded by her family and friends, and we wailed together, loudly and inconsolably. Yes! Here, finally, was a fitting response to irrevocable loss. Back home, where I live alone, it seemed natural to express my continuing grief in front of the camera, naked, at three AM one sleepless night.

In one stroke I had broken two bans on visibility—on grief and on the naked older female body—and I became curious to explore the way that older body occupied the world. What does it look like, and what can it mean?

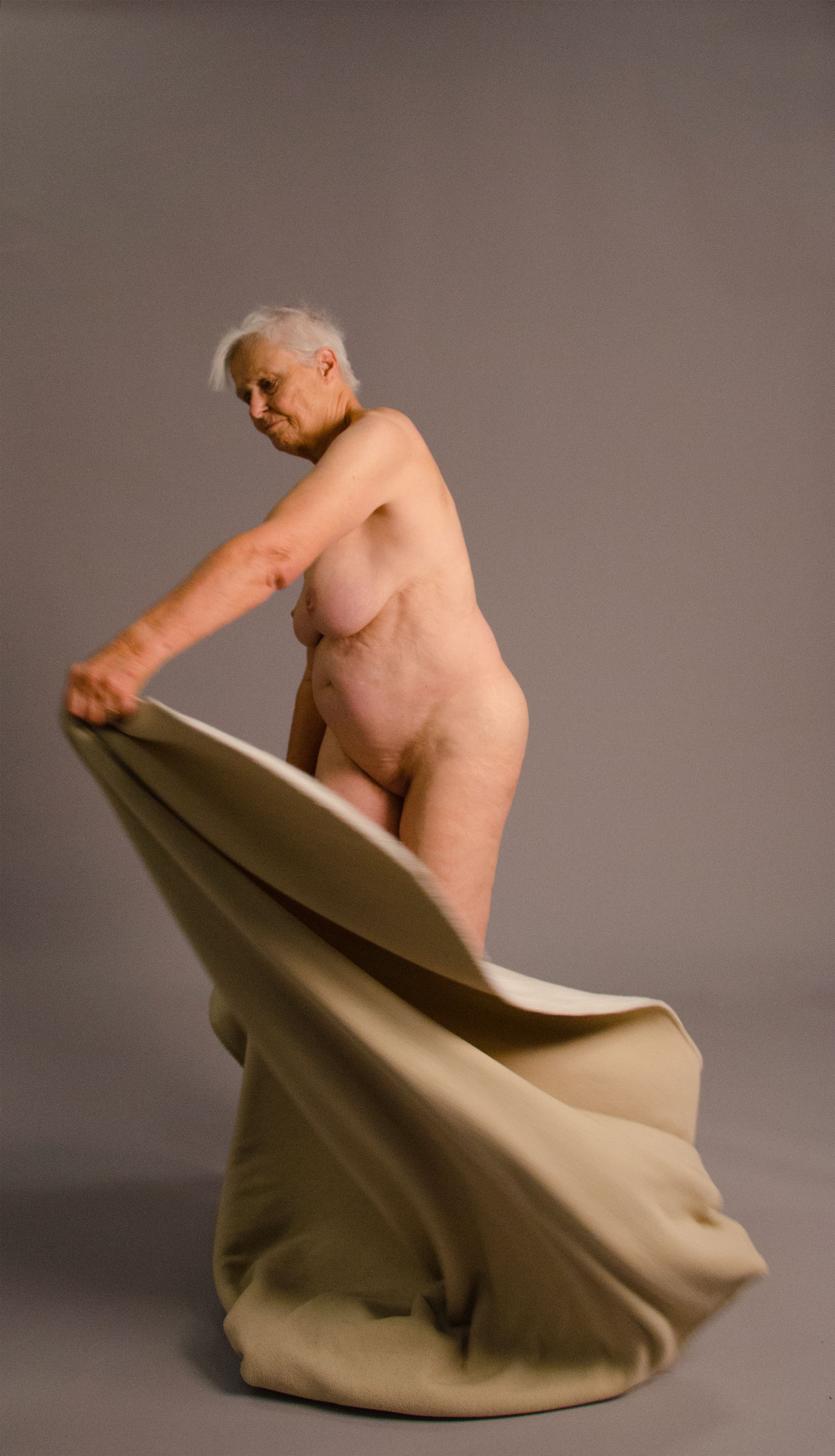

My first thought is that these images work against cultural conventions of beauty—youthful, apparently easy, but endlessly constructed—moving toward a recognition of the body as a palimpsest on which is drawn the history of effort and loss, pleasure and accomplishment, endurance, hope and inevitable decline. Removed from ideals about beauty, which elevate certain bodies above the simply human, or the simply real, it can draw attention to our place in nature and time.

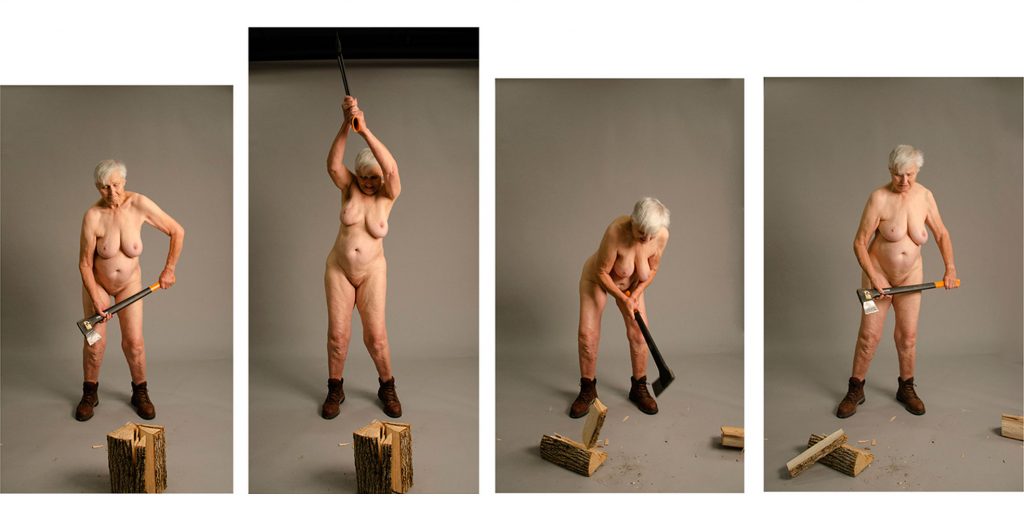

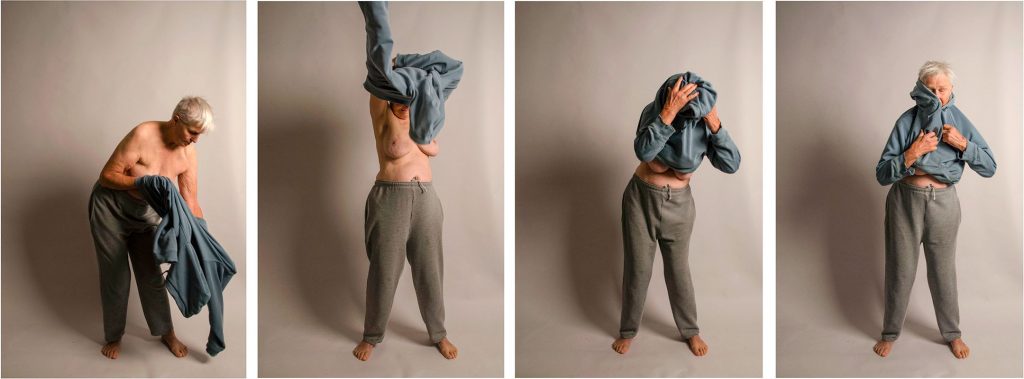

But the aging body, acted upon way beyond our control, is still active, engaged in the ongoing pushback against death. On some level, this series is a catalogue of my enduring capabilities, a private test of what I am still capable of. Yes, I can still jump, I can still sing and laugh, I can still split a log. My sister, skinny as a rail, still swam a few laps two weeks before she died. She fell, but wouldn’t let me help her up. “No, I can do this. It’s better if I do it myself,” she said.

There are inadvertent references here to classical sculpture that I relish, but I didn’t set out, like John Coplans, to heroicize or classicize these pictures. I don’t want to be anonymous, headless and faceless, as he chose to be in front of the camera. I am happy to own these images and this older body as flesh, not stone, as nature as well as culture.

I present them in series, as dissections of actions, in order to avoid “the pose.” The pose is always a reduction, a single idea, moment or self. I think of Barthes bemoaning photographs of himself as “heavy, motionless, stubborn . . . and ‘myself’ (as) light, divided, dispersed; like a bottle-imp . . .” It is impossible to resolve oneself into a singular image, a pose, when caught in the midst of jumping, and singing, and laughing. A pose is also imposed on a body, prescribed by social norms, a constraint and an obligation. I grew up masquerading as a girl for my mother’s camera, though I was and am more complicated than that: a tomboy, a divorcee, a lesbian, an artist, a retired professor, a friend, a lover as well as the mother of three children.

This project then aims to allow the body to speak unconsciously of its history and its place in the natural world.